How to Live: Our Responsibility to Live in Technicolor

This is a true story, as accurate as any story can be. And it is a real story about my daddy’s people. It is a real story about me.

Under the gaze of an alabaster George Washington, the lawmaker asks the patriot, "What you got?" The patriot blankly stared at the lawmaker, unable to respond immediately. Then the patriot, still shocked by what had just happened 20 minutes before, replied, "When I have something, I will let you know."

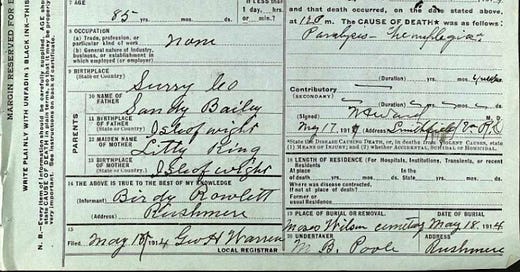

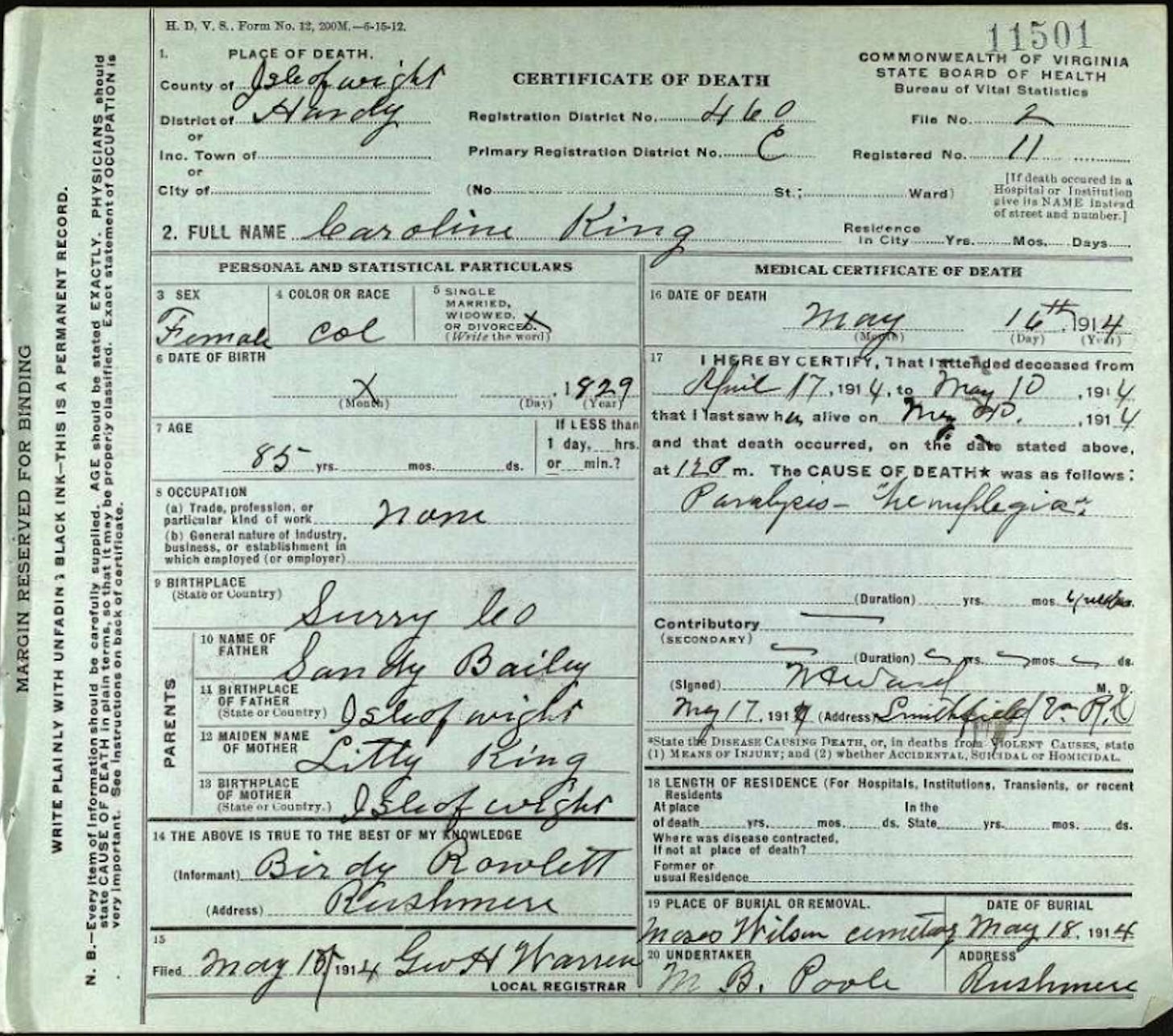

This is a story about dreaming in technicolor, high definition, and how it began in black and white. By the age of six, I was aware of my royal lineage—not royalty from a European monarchical feudal state, but from a matrilineal dynasty of beautiful Black people in the Tidewater. There are no books about us. There are no entries in encyclopedic volumes. There are a few newspaper clippings here and there about our recent lives. But there are a few records, vital records—mostly death certificates and census records—that spray-painted the earth, “I was here.” Our stories exist. Our stories still live.

Big Caroline—my grandmother—used songs to teach our lineage. She would say, 'These are your people. Remember it so you won't forget it.' She spoke in song when she talked about her family, our family. She would sing, “John Dickey, Knuckey, Plummey, Caroline the King.” I knew that her name was Caroline and I knew that my name was Caroline. I did not know how she got her name. But who was Caroline the King? And how did I get this name?

That answer lived about 200 miles away and had a 200-year story. The story of my beginning was born as Caroline King in 1829. Vital records and census data tell us a little bit about how others perceived her. Stories of the family, however, reveal more about how her people saw her. There is the story of Julian Derring, a confederate with whom she had a child, Mary Frances, the daughter, who was buried in the White cemetery. There is the story of the house that mysteriously caught fire, burning the family's wealth. There is another story about the decision point during the fire, where the choice was between saving a baby and saving money. There are stories of large feasts on the family land with a house on the road, and how it was such a big deal to have not just a home, but a house on the road. There are stories of hogs, a baseball diamond, and hangouts at Tyler’s Beach. There are stories about my grandmother singing to the sick people in the infirmary when she was a young girl. And playing with white children in the area and being friends until they learned how to treat black people in school. There was a story of starting a church on land that was passed down. There were families and clans that all lived in proximity with different surnames, including the Baileys, Blounts, Hills, Claggetts, Bradbys, and the Rowlettes.

There are the stories of Buck Ocie, my grandmother's father, a businessman with boats who ferried cargo up and down the coastal plain. There is another story about my grandaddy being my great-grandaddy’s driver. There are other stories of my daddy being able to go to the store and the white store clerk saying, “Those are Maude’s grandchildren, they can get whatever they want. Then there are names of the people who owned the stories—Caroline the King, Knuckey, Charlie Boy, and Jonathan (pronounced JO-nay-then), who lived in that little house down that road, just down there. There is Tootsie, Baby Sis, Grandpapa John, Charlie, Jenever, Corene, Lillian, Irene, and Doris. There is Chi-Chi, Barry, Claudette, and Simone. Some are still living, and others are living in the fullest of color on the other side.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Praxodox: Remaking Ourselves and Our Relationships to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.